“Of course I want to go back. I had everything in Syria. A job, a house, a car, and my heart. My family, friends, they all stayed there. They think I am safe, happy. But Turkey is not the end of my journey. I survive here. Look at me! I dye clothes all day long, it has been two years, and I cannot speak Turkish. When will I see my country again?” Hind, 26 years-old, Syrian refugee working in Fatih neighbourhood, Istanbul.

Currently running an exhibition in Istanbul, the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei compares the refugees’ journey to Ulysses’ Odyssey. Fighting Scylla and Charybdis, going from the frying pan into the fire, it took Ulysses 20 years to go back to his homeland, Ithaca. Seemingly to Homer’s hero, the idea of a return in Syria appears to be a crucial dream among the Syrian refugee community settled in Turkey.

“I studied British literature in Syria, and lived in Aleppo with my family. I used to be a volunteer at the Red Cross. However, the war started in 2012. Even though my father thought I was going to Istanbul to relax, it was quite clear for me that I will leave Syria for a long period of time. I took a taxi with another Syrian family and we crossed the border. At that time, it was already scary with all these checkpoints we had no idea of. I arrived in Istanbul. It has been 7 years now, and I am far from being relaxed.” Sofia, 35 years-old, Syrian refugee, English teacher in Istanbul, obtained Turkish citizenship.

March 2018 marked the seventh year of war in Syria. Since then, Turkey has welcomed 60% of the Syrian refugees population, representing the arrival of 3.5 millions of people and thus in an insanely short period of time. If Erdogan’s government has established refugees’ camps, only 10% of the Syrian refugee community lives there, whereas the overwhelming majority is dispatched between Turkey’s main cities such as Gaziantep, Hatay, Ankara, Izmir or Istanbul [Operational Portal Refugee Situation, 2018].

“You want to practice your Arabic? Well, no need to travel. You can just wander around Taksim square [1] or, better, just take the bus to Fatih neighbourhood. It is basically Syria, just go there and speak Arabic.” Mehmet, 35 years-old, Turkish, working in the neighbourhood of Cihangir, Istanbul.

The increasing tourism from Arab states as well as the adaptation of Turkish shopkeepers towards Arab tourists’ expectations foster an anti-Arab feeling in the city of Istanbul. Indeed, with the ongoing tensions happening between Turkey and Europe and the different terrorist attacks Turkey has faced, the country has seen its number of Western tourists decreasing, and the number of its Arab tourists increasing. This new wave of tourists has changed some popular neighbourhoods of Istanbul, frustrating some locals.

“Taksim square became a degenerated place. It was not like this. It was full of cafés, bookshops, concert halls, and independent cinemas. Now, all Istiklal street is about baklavas, shishas and prostitutes. Shopkeepers want to please Arab tourists, and the locals of the area just left the neighbourhoods for other ones: Karakoy and Kadikoy for example.” Deniz, 30 years-old, Turkish, employee in the banking sector.

To this feeling is added the general tiredness of the Turkish community towards Syrian refugees. Indeed, recent polls reveal that if Turks used to support Erdogan’s decision to open the doors to their “Syrian Brothers and Sisters” back in 2012, they do not anymore. Syrian refugees were always considered as temporary guests, and thus even legally knowing that the status of refugee is only given by Turkey to Europeans asylum seekers since the ratification of the 1951 Refugee Convention [Zoeteweij-Turhan, 2018].

However, it has been 7 years, and the situation does not seem to be a temporary one anymore. Turkey has spent 30 billions dollars for Syrian refugees, opened 27 camps, gave a free access to medical assistance for registered refugees, ensured school enrolment for Syrian children, allowed Syrian refugees to get a working permit, and has worked on Turkish asylum laws in order to give the Syrians the refugees’ rights which their status of guests prevented them to obtain [Mevlüt Cavusoglu, 2016; Zoeteweij-Turhan, 2018].

“Turks have more and more distaste for Syrian refugees. I feel they are fed up a bit and you can feel it in the streets, they have bad words towards us. They are overwhelmed. The current flow of refugees is too important for Turkey, its government and people. I cannot say we did not disturb anything. I am currently living with four guys in an apartment of one bedroom. But do they think I enjoy living like this? Really? ” Selim, 35 years-old, Syrian refugee, living in Tarlabasi, Istanbul.

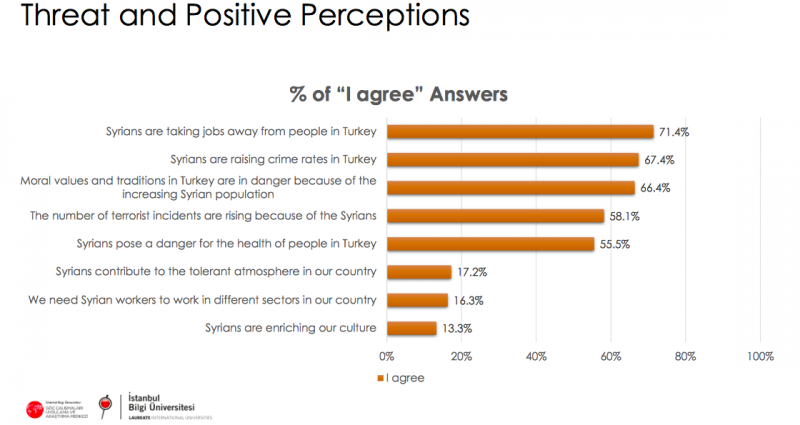

Moreover, the impact of Syrian refugees on the Turkish economy has negatively influenced Turks’ perception of Syrians. Ready to work for less than the national minimum wage (446.50 euros per month), or to live in an apartment with 4 other people for a higher rent, a growing part of the Turkish population living in the neighbourhoods welcoming Syrians considers that Syrian refugees steal their jobs and accommodations, making Turks’ living conditions harder.

“They believe we receive tons of money directly from the taxes they pay to the state. They do not understand that this money comes from European Union and that it is far from being a ton. They believe that we steal their jobs and apartments.” Sofia.

Crazy rumours are spread, blaming Syrians for all current Turkish despairs, highlighting the lack of clarity from Erdogan’s government on Syrian refugees’ situation. Indeed, it appears to be not properly advertised that the monthly and modest cash aid received by Syrian refugees reaches only 120 Turkish liras (30 euros), is allocated to unemployed Syrian refugees and is the result of a common fund created by the European Union, the United Nations, the Turkish Red Crescent and the Turkish government [Multeciler organisation, 2018].

This shift towards Syrian refugees has started to influence as well the stance of the political party on power, AKP (the Justice and Development Party). Erdogan took what he considered as an opportunity to boost its popularity and revive Turkey’s image. Indeed, by welcoming Syrian refugees, he added to his current Palestine’s hero status the one of the Syrian people’s saver. It is also a chance to differentiate himself from other regional powers such as Iran, ISIS, or Assad’s regime; as well as the one of taking a strong stance in the international realm, emphasising the failure of the EU in supporting Syrian refugees. Eventually, offering shelter to Syrian refugees with the promise of giving them the Turkish citizenship is a smart political move, ensuring new votes and new supporters for the coming presidential election in 2019.

However, the shift in Turks’ perception toward Syrian refugees has impacted Erdogan’s policies as well as Erdogan’s popularity, directly putting at risk his re-election. The fact that Erdogan has recently started to justify the Olive Branch operation in Afrin by asserting that it would lead to the return of some Syrians in Syria emphasises his temptation to go backwards regarding his political move towards Syrian refugees. Feeling the current annoyance of Turks, he tries to justify the crazy spendings of the current military operation at the Turkish-Syrian border, and thus to reassure some fringes of the Turkish population currently convinced that Afrin is a waste of men and money for the country.

Is the idea of Syrians coming back to Afrin even realistic? I do not think so. They would lack crucial economic opportunities, especially when considering the number of businesses owned by Syrians in Turkey: “Starting in 2013, Syrian firms consistently accounted for upward of 25 percent of foreign firms registered in Turkey, with the latter accounting for around 10 percent of the over 60,000 firms established annually in Turkey.” [Omer Karasapan, 2017]

“I learnt Turkish by myself because courses were too expensive. I got a job. I rent an apartment. I got the Turkish citizenship a few months ago. But I do not feel Turkish, I have no Turkish friends and I wish I could go back or settle somewhere else. Even if our situation is temporary in Turkey, we need temporary friends.” Sofia.

Contacts between the two communities are quasi non-existent. As Sofia underlined, the flow of refugees happened in Turkey, but nothing was organised to help them, guide them, integrate them – especially at the beginning of the Syrian civil war.

“When I arrived, everything was so different from my life in Syria. In Aleppo, we have nothing similar to the job application process with the resume and cover letter. We just call a friend and through networking we get jobs. For example, I would say to a friend my eagerness in finding a school teacher position, and Aleppo’s society will do the rest and someone will inform me of an opening here or there. It was a shock for me in Istanbul.” Sofia.

Sofia blames the lack of common grounds for her integration failure, and thus even though Turks and Syrians share a common history and religion.

“I believe the Syrians and Turks share the same culture. We shared the Ottoman empire, the religion, the food. They were so kind with Syrians at the beginning. But now, no. The problem with our integration in Turkey, it was not planned. We did not have the opportunity to meet each other, to spend quality time together. I learnt their codes and their language by myself, and I am still not sure I did correctly.” Sofia.

Learning Turkish is key in the integration process, and a crucial amount of international organisations were taking care of that. However, the aversion of Turkish government for foreign powers’ involvement in Turkish domestic affairs, as well as the numerous purges since the failed coup attempt of 2016 have both considerably disrupted humanitarian operations and life-saving economic support to Syrian refugees. In 2017, 560 foundations, 1.125 associations and 19 trade unions closed in a crackdown by the government, including multiple international humanitarian organisations such as Mercy Corps or DanChurchAid [Ross Longton, 2017].

“Turkish government gives the right to organisations to teach Turkish only if these ones have a licence from the gvt to do so, and of course, non-Turkish organisations do not get any. It is a shame for Syrians, and especially the kids because it jeopardizes their integration. We still try to teach Turkish, rebranding our Turkish courses on our leaflets and proposing activities in Turkish such as theatre. But we know we have to be careful.” Merve, 32 years-old, manager of a center helping Syrian refugees.

By imposing licences, Erdogan ensures the reinstatement of domestic organisations, his control on domestic affairs and conveys a clear message towards the West – always suspected of funding Kurdish militias or to start a conspiracy in the benefit of his Fetullah Gülen. However, the first ones suffering from these policies are the Syrian refugees who have started to believe that Turkey was not their Ithaca.

[1] Central district on the European side of Istanbul on which demonstrations generally happen (e.g. Gezi protests in 2013).